Medially luxating patella is a condition where the patella (knee cap) pops in and out of place in response to extension, flexion, or weight bearing of the knee joint. The disease is congenital in origin, resulting from inherited shallow patellar grooves (the groove in which the patella normally sits in), an inherited abnormally medially located tibial attachment point for the patellar tendon or both. The luxations almost always occur in the medial direction (toward the center of the body). For example, in the left limb, the tendency is for the patella to luxate to the right. The opposite is true for the right limb. The majority of luxating patella cases are bilateral.

Luxations cause inflammation and pain in the knee joint. Also, because the chief purpose of the patella is to redistribute tendon forces to best handle weight bearing and stress, patellar luxations tend to throw off the physics of the entire leg, causing excessive wear on the hips and ankles. This predisposes to degenerative joint disease in these other joints as well. What’s more, over time, as the luxations occur, the medial ridge of the patellar groove becomes worn, increasing the frequency of luxations. Eventually, if left untreated, the disease can progress to the point where the patella spends all of its time out of place. Patellar luxations are graded on the following scale:

Grade I: Patella luxates occasionally. Pain, discomfort, and lameness intermittent.

Grade II: Patella luxates regularly. Pain, discomfort, and lameness more frequently observed than normal gait.

Grade III: Patella spends more time luxated than in place. Pain, discomfort, and lamness almost always apparent.

Grade IV: Patella always luxated. Pain and discomfort severe to the point of severe to non-weight bearing lameness.

Medially luxating patella most commonly occurs in toy to small sized dogs. However, the disease is occasionally reported in larger dogs and in cats. Treatment is surgical and geared toward deepening the patellar groove and anchoring the patella laterally. The most accepted surgical approach in small dogs is known is the trochleoplasty, tibial tuberosity transposition. The doctors of Grant Animal Clinic are trained to recognize, diagnose, and surgically repair injuries and malformations of the canine knee through clinical history, orthopedic examination, and digital x-rays. Dog knee surgery is a special interest of Grant Animal Clinic General Partner and Attending Veterinarian, Dr. Roger Welton. Prior to veterinary school graduation, Dr. Welton completed two orthopedic surgery rotations at the prestigious Animal Medical Center in New York City (in addition to his required orthopedic clinical rotation at University of Illinois). In addition to performing dog knee surgery since he graduated in veterinary school in 2002, Dr. Welton has also since earned two post doctoral certifications in reconstructive surgery of the canine knee. He has since trained all of the Grant Animal Clinic doctors in the most cutting edge dog knee surgery techniques, using the most state of the art surgical equipment and hardware.

Trochleoplasty

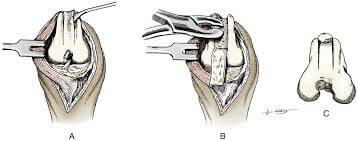

Deepening of the trochlear groove, or trochleoplasty, can be accomplished with a variety of techniques. A chondroplasty technique involves cutting out a taco-shaped wedge of cartilage, removing a small portion of bone beneath it, and then replacing the cartilage. The result is a deeper groove. This procedure can only be performed on very young dogs, because their cartilage is thicker.

Trochlear Recession

Trochlear recession involves cutting out the cartilage and bone in such a way as to create a deeper trough. This trough will then fill in with scar tissue over time. Because this scar tissue is not as good as cartilage for joint function, this technique has given way to others that attempt to preserve normal cartilage. It can, however, be useful in carefully selected cases.

Wedge recession creates a taco-shaped piece of cartilage and underlying bone. Then, the bone below the wedge is removed and the wedge is replaced, forming a deeper groove. Block recession is identical in principle to wedge recession, except that a rectangular piece of cartilage and bone, rather than a wedge, is removed.

Tibial Tuberosity Transposition

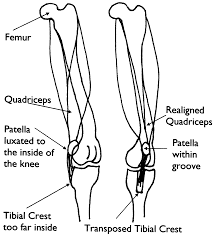

The kneecap attaches to the lower leg via its patellar tendon at a bony site called the tibial tuberosity. Many times this site forms abnormally on the inside, as with MPL, or on the outside, as with LPL. In this procedure, the surgeon moves the tibial tuberosity back into proper alignment and secures it in place with a pin or wire. Realigning the joint, kneecap, and tendon prevents dislocation from recurring.

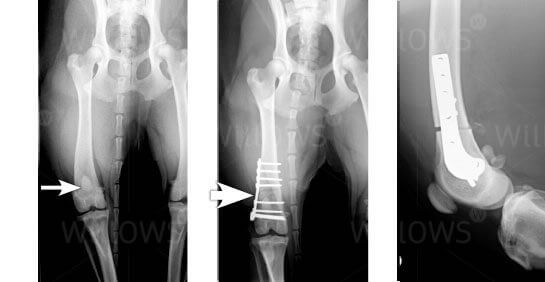

Osteotomy

In severe cases, with malformation of the tibia or femur, corrective bone cuts known as osteotomies may be required.

Prevention:

Early detection and correction is the best way to prevent severe lameness and dysfunction. Breeding affected animals is unethical, as medially luxating patella is a genetically inherited condition.

Post-Operative Rehabilitation & Care

Following surgery, the goal is to have the patient using the limb as quickly as possible. As such, we do not generally recommend any kind of bandaging or splinting of the operated limb. Some more stoic varieties of dogs will drop the toe down and gingerly weight bear within a few hours of surgery. For others, it may take 1-5 days before they are willing to drop the toe down.

Our general recommendation following medially luxating patella surgical repair is to leash walk the patient very slowly 4-5 times daily. The slower the patient walks, the more challenging it is to walk on three legs, the more likely he may be to drop the limb down. With less stoic (and stubborn) varieties of dogs such as certain toy or small breeds, it can be particularly challenging to coerce them to use the limb. This is problematic because it significantly slows the healing process, contributes to continued muscle atrophy, and can begin to lead to contraction of the hamstring muscles as they are held in constant flexion. For these cases, we have techniques and exercises we can recommend to overcome this obstacle.

Class IV Therapy Laser

Classic IV therapy laser gently infuses low level photons of energy into cells and tissues. The resulting physiological effect at the cellular and tissue level is called photobiomodulation. This process dilates arteries and arterioles to bring oxygen and nutrient rich blood to areas. Arterial blood also brings healing cells to help clean up and remodel damaged cells and tissues.

Photobiomodulation also dilates veins and venules, as well as lymphatic vessels. By stimulating venous circulation, this helps to stimulate the removal of inflammatory debris and stagnant blood in a compromised areas. By dilating lymphatic vessels, we potentially stimulate the drainage and replenishment of interstitial fluid, the liquid medium cells and tissues of the body are housed within.

Therapy laser also stimulates the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) within cells. ATP is the powerhouse of the cell by from which it derives energy to perform its physiological functions. By increasing ATP within cells, therapy laser serves to provide cells a jolt of energy in the form of increased ATP to enhance cellular repair and the rebuilding of tissues. Protocols vary, but I generally recommend 6 treatments directly over the incision over a course of 3 weeks.